A friend called me this morning to ask a question about yeast. She is an experienced home baker, but, like many people, has always used Active Dry Yeast. Because so many people are baking while they are in lockdown, yeasts and flours are becoming hard to find. A mutual friend gave her some Instant Dry Yeast, but she wasn’t sure how to use it in place of the Active Dry yeast she it used to.

I thought (actually, my wife thought) other people might be in the same situation, so here’s a short explanation of some different kinds of yeasts you might have access to, and how to convert between them if you need to.

The main types of yeast that you are likely to run into are Active Dry Yeast, Instant Dry Yeast and Quick or Rapid Rise Yeast. Active Dry and Rapid Rise are the main kinds of yeast that you can purchase at the grocery store in the little packets that I always used to make a mess of when I tried to tear them apart.

The main difference between these is:

Active Dry Yeast is milled to a larger size than instant yeast. Therefore it needs to be dissolved in water before using. When I first learned to bake, long, long ago, this is what I used. Most home bakers proof the yeast before baking. Proofing is the process of dissolving the yeast in water with a little carbohydrate – usually sugar – dissolved in it, and then waiting until it bubbles to prove it’s alive.

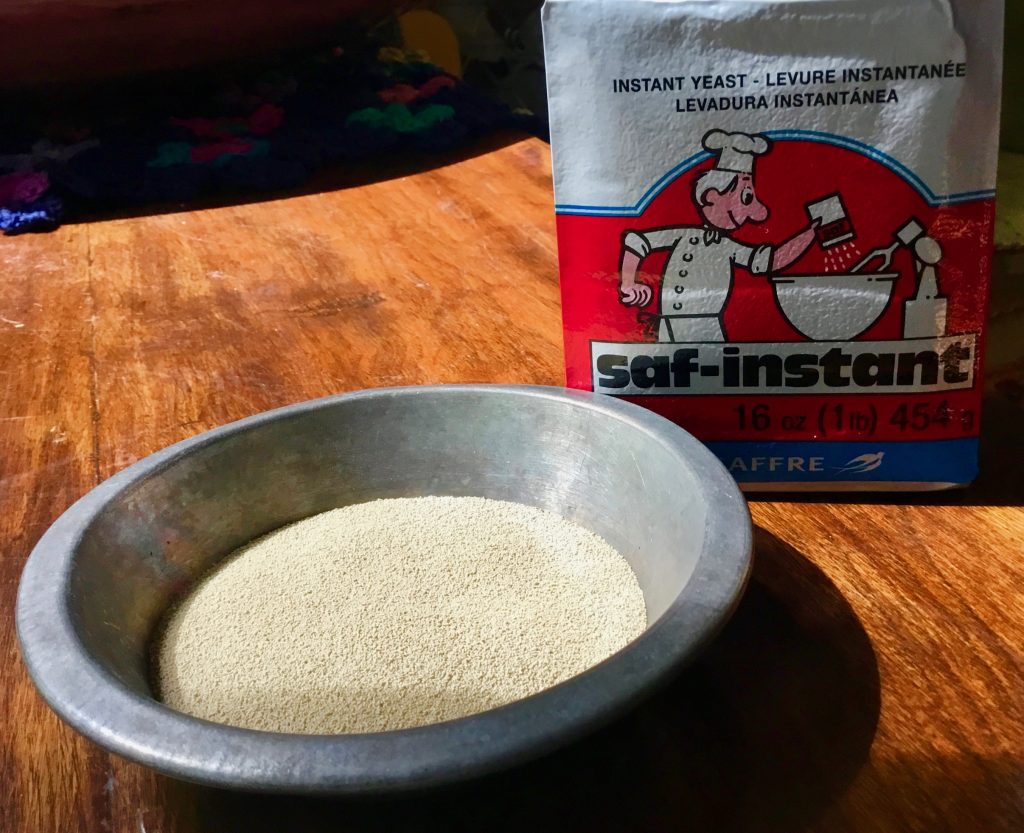

Instant Dry Yeast is milled much more finely so that you can mix it directly into the flour and other dry ingredients, and then add the liquid ingredients and you’re good-to-go. There’s no need to proof it. I have read that instant yeast contains a higher percentage of live yeast than Active Dry. I’m not sure if this is true, but it certainly behaves as if it is. SAF Red instant dry yeast is the yeast that I use for almost everything, as does just about every professional baker I know.

Quick Rise or Rapid Rise Yeast are milled finely, like Instant Dry. They also have enzymes and other things added to turbo charge them with the idea of making your dough rise faster. As I understand it, you really can’t proof rapid rise yeast as this will make them much less effective.

Osmotolerant Yeast , the most common of which is SAF Gold, is specially designed to be more reliable when making breads with a high sugar content (more than 10% of the flour weight). I use it when making sweet challah, or croissants, or other sweet breads.

Which to use?

If you can, choose one you like and get to know it and use it for everything. If you’ve always used Active Dry yeast and know how it behaves, then there’s no reason not to continue using it. The yeast you know is almost always going to give you better results than the yeast you don’t know. When I’m using commercial yeast, I exclusively use SAF instant yeast.

Switching between Active Dry and Instant yeast

I like to keep things simple, so I use the same amount of yeast no matter which I use. If I were using Active Dry I would expect it to take a little more time to rise than if I’m using Instant. There are so many things, primarily temperature, that determine when your dough is done rising I wouldn’t put a number on it, but just be ready for it to take a little bit longer.

If, for some reason that I can’t think of, you want things to take the same amount of time, you can find conversion tables, but that seems like a lot of trouble.

Of course, if you can’t find any commercial yeast, you can make a sourdough starter, as our ancestors have done for generations. I’ll put up a post soon about how to make and use your own starter.

If you’re not done reading about commercial yeast, here’s a great article on the King Arthur Flour site about which yeast to use, where they show you their testing.

I hope this is helpful. Have a good bake!