Normally I would say that paying attention to your bread at every stage, and being present when it’s time to take action, are two of the most important qualities in a baker. Bread dough is a living thing and, if you are listening, it will tell you how it’s doing and what it needs. The key is to be able to pay attention, to listen (metaphorically), to what the bread needs, and then to do that thing.

To say that I was distracted and not paying attention, and not present when I needed to be during my last bake is a fantastic understatement. As seems to be clear at the moment, the world has been turned upside down and everything is not the way we thought it was a couple of months ago, and as a result of my being completely distracted and not present when things needed to happen, I made one of the best loaves I’ve ever made.

Counterintuitive, but true.

I’ve been doing some recipe testing for Fougasse, a wonderful French flatbread. First day I made a loaf using a Paté Fermenté (a kind of pre-ferment). Day two, yesterday, was going to be another test using a sourdough as a pre-ferment (as opposed to sourdough as the leavening agent). I had prepared the levain the night before so I would be ready to go in the morning.

Enter reality…

Because of the spread of the novel coronavirus, most of the Bay Area counties had been given “Shelter In Place” orders the previous day, and rumor had it that it was going to happen to us here in Sonoma County soon, so I wanted to get all of my “out in public” things done before the lockdown. My 84 year old mother needed some food and medicine picked up, and since they are recommending people over 65 stay in as much as possible, I was clearly going to spend the day errand running (which I was happy to do, mom).

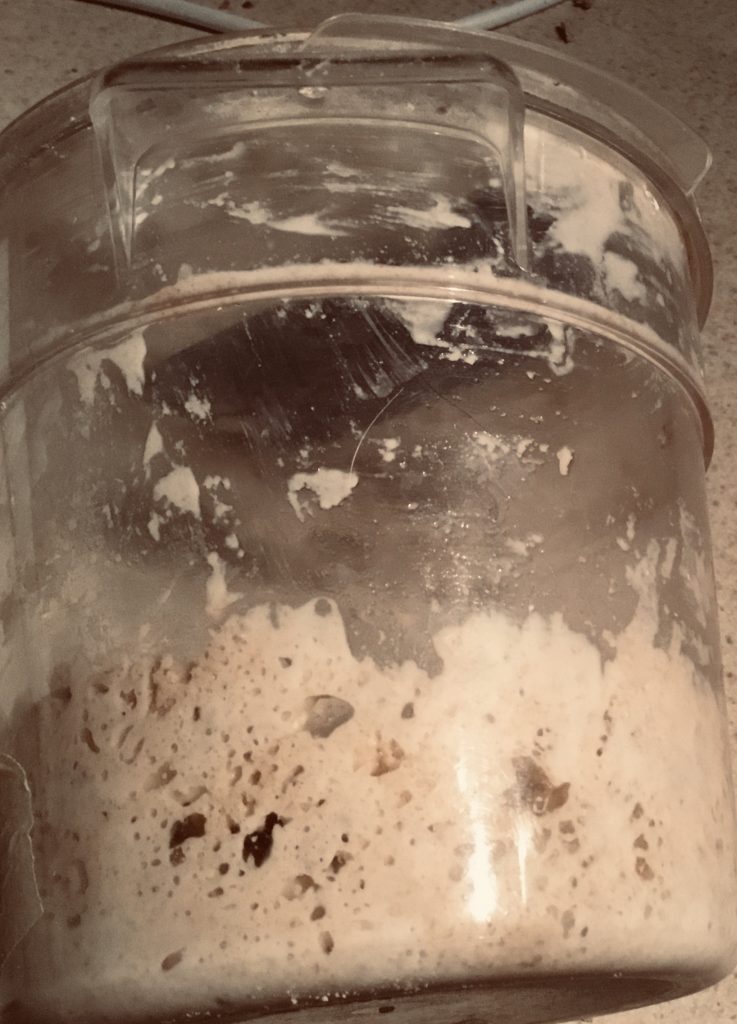

My levain – which was looking perfect and ready to go – sadly had to hold on until later. I popped it into the fridge as I headed out the door. This is something I never do; I never retard a levain. When the levain is at that perfect moment it wants to be used (as do we all). But retarding in the fridge slows fermentation down, and since I don’t like throwing things out, I figured I’d just see where the levain was when I got home and figure out what I was going to do then.

Off I went into battle with seemingly all of Sonoma county, trying to buy whatever they could before the world came to an end. At least that’s what it felt like.

Six hours later I was home again and after a thorough decontamination, I pulled my levain out of the fridge to finish what I’d started the night before. Sad face. It was definitely a bit over-fermented – a little too acidic and starting to collapse a bit – but not to be deterred, I decided to proceed.

I put the dough together, put it in it’s tub for bulk fermentation, and sat down to obsessively read about coronavirus. The bulk fermentation was supposed to be around two hours, so I set a timer for 90 minutes (I always set the timer early so I don’t miss The Moment).

I don’t know what happened, either I hadn’t actually set the timer, or it went off and I was just too distracted to notice (wouldn’t be the first time). Two-and-a-half hours later I looked up and let out an expletive when I realized that I had forgotten all about my dough and it had over-fermented, once again.

Again, like the levain, it wasn’t too bad, and I figured I’d continue on. I wasn’t expecting much out of this loaf, but even bad fresh bread is better than no fresh bread.

As I put the bread in the oven, it was clearly over proofed, wet and slack and flattening out before my eyes. “Crackers are good too”, I said to myself.

But in the oven it transformed into something beautiful and unexpected. The parts that completely degassed got crunchy while some of thicker bits, while they didn’t get a lot of oven bounce, were certainly soft and delicious. The cheese, which I had cut into cubes rather than grate, pushed to the surface and crisped up like fried cheese (something I’m particularly fond of).

These loaves were a lovely gift at the end of a long day, and a reminder that sometimes not being in control gives you something beautiful and unexpected. I find this a useful reminder in difficult times when I am particularly aware that we don’t have much control over anything.

Now I have to figure out how to make them again intentionally.

Be safe everyone.